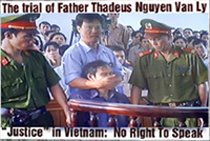

The U.S. Congress has entered the fray involving what one congressman has called the "kangaroo court conviction" of Father Nguyen Van Ly, a Vietnamese Roman Catholic priest by the Hanoi regime.

A resolution authored by U.S. Rep. Chris Smith, R-NJ, calling for substantial human rights reforms in Vietnam was overwhelming approved this week by the House Foreign Affairs Committee during their first mark-up since Vietnam’s conviction of Father Ly.

Earlier this year, the parish house of Father Ly — a former prisoner of conscience who spent more than 13 years in prison — was raided. Father Ly was moved to a remote location and placed under house arrest. Father Ly is an advisor to "Block 8406" - a democracy movement which started last April - and a new political party, the Vietnam Progression Party.

On March 30, 2007, Father Ly was sentenced to 8 years in prison for distributing "anti-government" materials.

Father Ly was among a number of dissidents swept up in a recent crackdown in Vietnam. In March, Vietnamese police arrested another member of "Block 8406," principal spokesperson for the Vietnam Progression Party and the founder of the Vietnamese Labor Movement, Le Thi Cong Nhan. On the same day — March 6, 2007 — Vietnamese police arrested one of Vietnam’s few practicing human rights lawyers, Nguyen Van Dai.

"Father Ly’s sham trial proves once again that the regime in Hanoi is not committed to the human rights reforms they promised as a precondition for normalized trade relations. It is not enough for the Government of Vietnam to talk reform — they must also show progress through their deeds," said Smith, who actively opposed the granting of normal trade relations with Vietnam.

Smith added: "Recent government actions show that Vietnam is moving backwards, not forward. This resolution reinforces our unwavering commitment to human rights reform in Vietnam and demands that the regime in Hanoi cease their persecution of dissidents."

"There is no compromise, no halfway point when it comes to basic human rights. We must send a clear message to the Government of Vietnam that there is no place in modern society for their conduct," Smith said.

Introduced last month, Smith’s resolution (H.Res. 243) calls on the Government of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam to immediately and unconditionally release political prisoners and prisoners of conscience, including Father Ly and those who have been arrested in a recent wave of government oppression. The resolution also calls for the Government of Vietnam to comply with internationally recognized standards for basic freedoms and human rights.

"I have met with Father Ly and a number of other dissidents who are now behind bars or under constant surveillance and harassment in Vietnam. The bullies in Hanoi continue their systematic and brutal politically motivated crackdown on democratic activists and this must end," Smith said.

"Father Ly’s arrest and conviction are purely political, a shameful attempt to silence him and intimidate anyone else who dares to speak out against the government. We have an obligation to speak up for Father Ly and other dissidents who are persecuted in Vietnam. Now that the Committee has spoken through this resolution, it is time for the full House to immediately pass it and give a voice to the dissidents in Vietnam," Smith added.

A similar Smith-authored resolution condemning human rights abuses in Vietnam and calling on the Government of Vietnam to release political prisoners passed the U.S. House of Representatives in 2006.

In another development affecting Protestant denominations in Vietnam following the March 29, 2007 sentencing of Ly to 8 years in prison for distributing "material harmful to the state," two Protestant lawyers charged with the same "crime" are expected to face equally harsh sentences in what Human Rights Watch has called the harshest crackdown in 20 years.

Attorney Nguyen Van Dai, 38, a member of the main Hanoi congregation of the legally-recognized Evangelical Church of Vietnam (North), or ECVN (N), since 2000, was arrested on March 2, 2007.

He had been documenting human rights violations in Vietnam.

According to Pastor Au Quang Vinh of the Hanoi church, a second lawyer, Le This Cong Nhan, 27, was also arrested in early March. She had just completed a doctrine course for new believers at the same church in preparation for baptism.

Both lawyers also have friends among Vietnam’s house churches. Dai is also a member of Advocates International, an organization which brings together Christian human rights lawyers from many countries.

Authorities have prohibited Dai’s wife, Khanh, from visiting him, and her home phone and cell phone services have been cut. A Christian source also said that police have been trying to incite neighbors against her.

An 80-year-old lawyer, Tran Lam of Hai Phong, is willing to defend Dai, but contrary to Vietnamese law, police will not allow him to have contact with Dai, sources said. They added that authorities prohibited Dai from taking his Bible or some of his medications with him.

Following the arrests of Dai and Nhan, Vietnam’s official press painted the two lawyers in unflattering terms. On March 14 and 17, the An Ninh The Gioi (World Security) newspaper, official organ of the Ministry of Public Security, carried a four-page, two-part article showing the government’s view of the two lawyers and the case against them.

Both lawyers are described in the state-controlled newspapers as very average individuals who could not hold a job after graduation from law school. Revealing more than intended, the article describes Dai getting into law school without sufficient grades because of his father’s influence as a Communist Party member.

The report paints both lawyers as criminals. Dai is said to have received a U.S. State Department scholarship to study advocacy in the United States and to have later helped to study Internet and computer security in the Philippines. He is accused of distributing "alleged infractions of religious liberty" to Vietnam’s enemies aboard.

Nhan is accused of assisting in the establishment of an "independent trade union." Both are accused of fraternizing with other dissidents in the country and with counter-revolutionary exiles abroad. Both are accused of teaching students and other young lawyers "the values of Western human rights."

They are also accused of involvement in a pro-democracy movement called Bloc 8406, begun a year ago. Roman Catholic priest Father Ly has been accused of helping to found Bloc 8406. Ly, 60, who had been under house arrest since February, has spent 14 of the past 24 years in prison.

Dai is accused in the article of getting money from counter-revolutionary exiles abroad and of stealing US $80,000 from the ECVN (N). Church leaders told Compass that they were not aware of any such money.

Dai’s activities in human rights advocacy, beyond religious freedom, have become controversial in Vietnam’s evangelical community. Many Vietnamese Protestants believe it is too risky to challenge the political monopoly of the state in such matters. Some are even willing to pay the high price of silence on other human rights in exchange for supposed improvements in religious freedom.

The ECVN (N) leadership reportedly indicates some reservations about Dai’s dissident activities. In an apparent leak to the government of a copy of its executive committee minutes of June 6, 2006, the An Ninh The Gioi article says the church committee moved to remove Dai from the church’s legal committee for fear that his involvement in human rights work would "damage the reputation of the church."

The official newspaper article tries to inextricably link together Dai, the ECVN (N) and the U.S. government, in keeping with the long-held fear by Vietnam’s authorities of "peaceful evolution." In this paradigm, Vietnam says that after its erstwhile enemies lost the war in 1975, they have then turned to "democracy, human rights and religious freedom" to try to overthrow the communist revolution. All three factors have been invoked to justify the crackdown.

The U.S. State Department, which strongly defended removal of Vietnam from its list of the worst religious liberty violators last November, has been witness to some recent events that could evoke second thoughts. U.S. Ambassador to Vietnam Michael Marine recently spoke diplomatically about the crackdown and the rights of Vietnam’s citizens to engage in peaceful expression of their views on human rights and political matters – but then things turned nasty.

On April 6, 2007, the ambassador invited the wives of four imprisoned dissidents, including Dai’s wife, as well as the mother of Nhan, to a reception at his home in Hanoi to meet U.S. Congressional representatives. The police prevented three of the women from even leaving their neighborhoods and stopped the other two women with a large police contingent outside the ambassador’s home.

According to a report from The Associated Press from Hanoi on April 6, the usually conciliatory ambassador complained strongly about this to Vietnamese Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Phan Gia Khiem.

"You had 15 men surrounding two women, speaking in loud voices and grabbing their upper arms and tugging them," Marine reportedly said. "I told them it was absolutely wrong for women anywhere to be treated that way."

A long-time Vietnam observer remarked, "People may have growing freedom to ’believe,’ but when Christian-motivated activists act on their belief that the dignity of humankind leads to inalienable human rights, they are still prosecuted in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, where peaceful human right advocacy is considered a criminal offense."

The Vietnamese Assemblies of God house churches first called on Dai in 1999 to try to use legal means to fight the arrest of a house church leader, Mrs. Nguyen Thi Thuy, in Vinh Phu Province. That appeal was unsuccessful, but Dai became a believer through the Christian contacts he met in the process.

Shortly after, Dai and his wife became active at the Hanoi Evangelical Church at 2 Ngo Tram Street.

Dai gained notoriety among authorities in Vietnam and some recognition abroad for his defense of "the Mennonite six" in 2004 and 2005, a case he lost in spite of superior arguments due to the lack of an independent judiciary in Vietnam. Two of the six accused Mennonites, however, were released before the end of their sentences because of strong international advocacy.

Nhan, recruited by Dai into his law firm, became a Christian in 2006. She and her mother had been Baha’i believers but were expelled for "going against Baha’i beliefs and doctrine." Nhan was supposed to be baptized this past Easter.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment