Extract from the HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY Hansard of 2 May 2007

Ms CICCARELLO (Norwood): My question is to the Minister for Multicultural Affairs. Can the minister inform the house of the significance of the anniversary of the fall of Saigon to the South Australian Vietnamese community, and indicate the implication for human rights in Vietnam today?

The Hon. M.J. ATKINSON (Minister for Multicultural Affairs): I thank the member for Norwood for an important and timely question, which touches on issues of human rights. These should be the concern of every South Australian. On Monday 30 April we marked the 32nd anniversary of the fall of Saigon. It was a particularly poignant day of remembrance; 30 April 1975 was the day that the North Vietnamese forces invaded Saigon, the capital of the Republic of Vietnam, and established a communist government, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

The Hon. M.J. ATKINSON (Minister for Multicultural Affairs): I thank the member for Norwood for an important and timely question, which touches on issues of human rights. These should be the concern of every South Australian. On Monday 30 April we marked the 32nd anniversary of the fall of Saigon. It was a particularly poignant day of remembrance; 30 April 1975 was the day that the North Vietnamese forces invaded Saigon, the capital of the Republic of Vietnam, and established a communist government, the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

The anniversary was formally recognised on Sunday, and I attended two functions arranged by our Vietnamese Australian community. They were both sad occasions. Our valued and hard‑working Vietnamese-Australian community, who lost so much and risked all for their beliefs, remain truly troubled and distressed about the events of 1975 and what has occurred subsequently.

The communist regime in Vietnam now rules with an iron fist. I speak with first‑hand knowledge as, together with you, Mr Speaker, and my parliamentary colleagues—the members for Norwood and Morialta—I visited Vietnam on a study tour last August. Communist Vietnam today is an elite of about 2 million Communist Party members ruling and riding roughshod over 80 million of their countrymen. Imbued with absolute paranoia, the Communist Party reacts swiftly and sometimes violently whenever it perceives that its authority is being challenged. Indeed, when the Socialist Republic of Vietnam became aware of the unveiling of the Vietnam war memorial here in Adelaide, it got in touch with Alexander Downer and made sure that no federal Liberal government officials attended the unveiling.

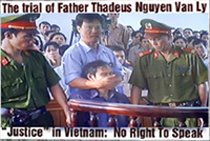

One of the saddest examples of this paranoia is the subject of the T‑shirt I have been wearing today and yesterday. The image is that of Catholic priest Father Nguyen Van Ly and it clearly shows the loss of human rights in Vietnam since the fall of Saigon. Members may have seen the quarter-page advertisement in The Australian newspaper last Friday alerting us to the fate of Father Ly. Father Ly is 60 years old, he is a peaceful man and has long been an advocate for religious freedom in his country. For this he has suffered periods of house arrest.

One of the saddest examples of this paranoia is the subject of the T‑shirt I have been wearing today and yesterday. The image is that of Catholic priest Father Nguyen Van Ly and it clearly shows the loss of human rights in Vietnam since the fall of Saigon. Members may have seen the quarter-page advertisement in The Australian newspaper last Friday alerting us to the fate of Father Ly. Father Ly is 60 years old, he is a peaceful man and has long been an advocate for religious freedom in his country. For this he has suffered periods of house arrest.I have some first‑hand experience of this. When our delegation visited the Archbishop of Hue last year, Father Ly was confined to the archbishop's house. As we arrived, Father Ly was surrounded by plain-clothes police to prevent him from making any contact with our delegation. In February Father Ly was re‑arrested, charged with distributing anti-government material—and I can assure you that is milder than anything that is said about the Rann government on talkback radio in Adelaide—and being in contact with anti-government organisations overseas. Presumably that includes the parliament of South Australia.

On 30 March Father Ly was put on trial—a kind of trial. When he tried to speak he was gagged. This image shows Father Ly in court guarded by two soldiers. A third plain-clothes official has his arm around Father Ly's neck and his hand over his mouth, preventing him from speaking. That is a fair trial in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, apparently! Father Ly was found guilty, of course, and sentenced to eight years' imprisonment.

Sadly, many other citizens of Vietnam suffer likewise. Leaders of religious bodies not under state control, like the Hoa Hao Buddhists, journalists, independent unionists and others, are all in gaol or under house arrest for exercising what we regard as the most basic human rights and freedom of speech. There is no freedom of speech in the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, nor is there freedom of association, press or religion. Those who speak out are persecuted. I encourage the house to reflect on this tragedy and injustice and to let our Vietnamese-Australian community know that our thoughts are with them.

Moreover, I call upon all members to express their concerns directly to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in Canberra. Father Ly must be released. Vietnam must be made aware that this continuing and blatant abuse of the most basic human rights will not go unnoticed.

Honourable members: Hear, hear!

Honourable members: Hear, hear!

No comments:

Post a Comment